Who Is L.W. Wright, Known For Decades As 'NASCAR's D.B. Cooper'?

At the 1982 Winston 500 in Talladega, a completely unknown driver named L.W. Wright managed to finagle his way into the race, then disappeared into legend.

Everyone loves a good mystery and surely racing fans are no different. Well in honor of NASCAR's historic 75th season, let's look back at one incident that, for decades, stood as one of the league's most enduring whodunits.

The story dates back to May 1982. The setting: the Winston 500 at the Alabama International Motor Speedway, though current fans would more easily recognize both the race and the track as Talladega.

The race featured all the stock car royalty of the day: Dale Earnhardt Sr., Darrell Waltrip, Bobby Allison, Richard and Kyle Petty, and Bill Elliott, just to name a few. But also on the track was one driver who was a complete unknown. A man who, until just last year, would disappear into the ether as quickly as he had unexpectedly arrived that day: L.W. Wright.

RELATED: NASCAR’s Kyle Larson And Wife Katelyn Welcome New Baby Boy To The Family

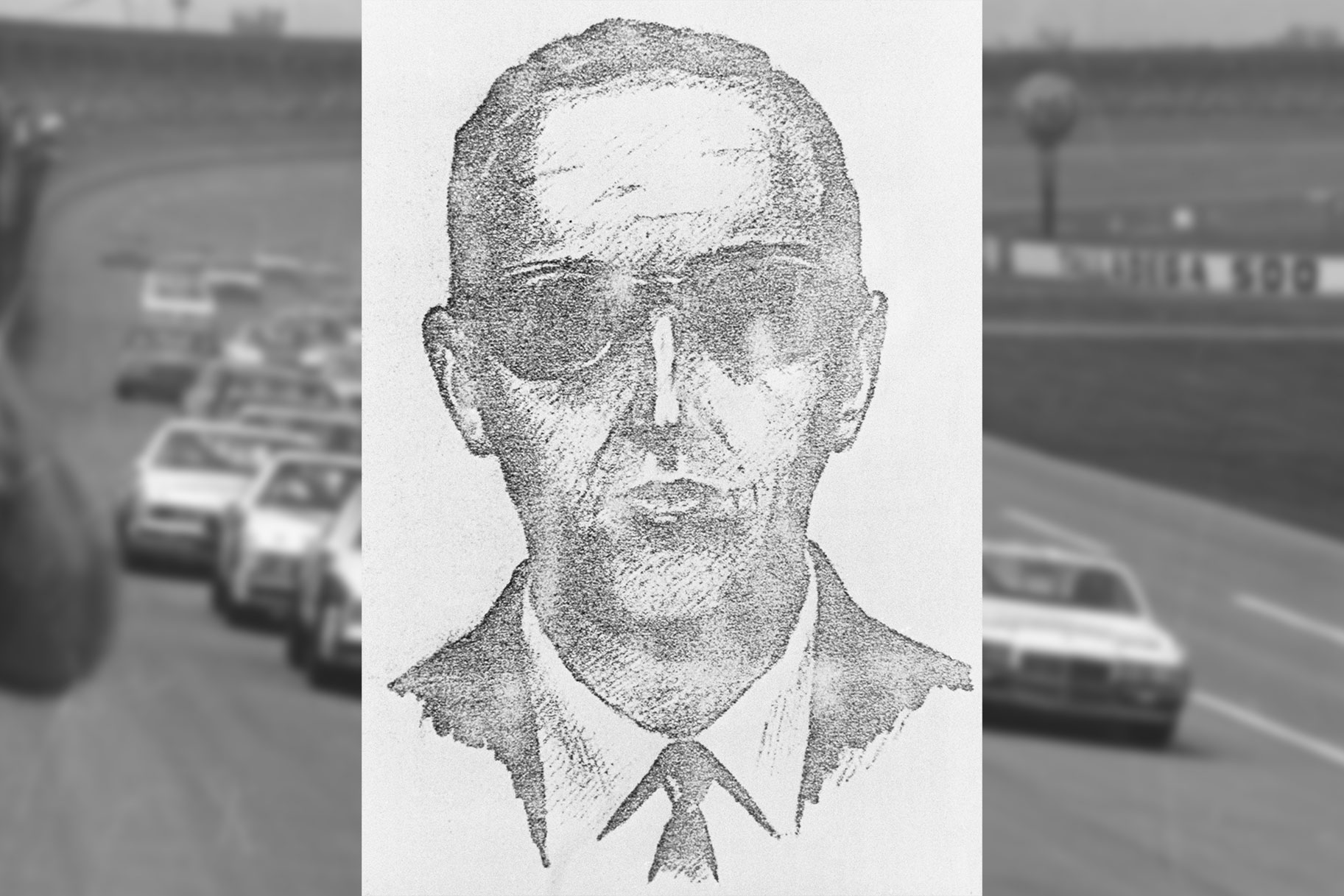

The mystery man's presence that weekend, and how suddenly he vanished following it, would draw parallels to D.B. Cooper, the infamous plane hijacker who commandeered a Portland-to-Seattle flight in 1971, securing $200,000 in ransom money and a parachute before leaping from the plane and into American folklore.

L.W. Wright Emerges From Out Of Nowhere

Wright’s saga began in Nashville, Tennessee after he notified a local newspaper that he would be racing at the Alabama Superspeedway, having secured a racing sponsorship from country music stars Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings and T.G. Sheppard, according to ESPN. Wright claimed to be a 33-year-old driver with 43 starts in the Busch Grand National Series, now the Xfinity Series, to his credit.

He purchased a NASCAR license for $115 and shelled out another $100 for an entry fee into the Winston 500.

According to newspaper reports at the time, cited by ESPN, Wright then convinced Bernie Terrell, the owner of a Nashville-based marketing firm, to loan him $30,000 to buy a race car, plus funds for additional expenses like transportation to Alabama.

Wright would go to purchase a car – a legit Monte Carlo – through another Tennessean named Coo Coo Marlin and his son, Sterling, who'd go on to carve out a successful NASCAR career. The Marlins accepted $17,000 in cash from Wright as well as a check that covered the remaining $3,7000. Sterling even agreed to accompany Wright down to Alabama to serve as a pit crew chief, but that's when red flags began to emerge

Wright’s Story Begins to Unravel

One of Wright's mistakes was claiming to have scored several victories on short tracks located in Virginia; however, Sterling Marlin recounted to ESPN that he unable to name prominent racers who had competed on those same short tracks. Sterling also said that Wright would pepper him with a host of basic car questions that any legit stock car racer should’ve known.

Adding to a growing swell of skepticism was the fact that, after Wright's supposed sponsorship by Sheppard, Haggard and Jennings made the media rounds, Sheppard released a statement that he'd never heard of the man, prompting Wright to backtrack on some of his claims. He said he'd simply jumped the gun on announcing a possible sponsorship, and explained that his previous racing experience was on tracks used in the Busch Series, not in the actual circuit, according to ESPN.

Reflecting on the mystery, Ken Martin, senior manager of archive development for NASCAR, recalled to Virginia news station WCVB how the initial circumstances surrounding Wright’s story didn’t quite add up from the jump.

“There's a gentleman named Gary Baker who was the promoter of the Nashville track, part owner of the Bristol track, and Gary's like, ‘I've never heard of this guy [Wright], and it just so happens I represent T.G. Sheppard,’" revealed Martin.

Wright's Brief Moment In The NASCAR Spotlight

But, arriving in Talladega with a legitimate NASCAR license, entry fee and car, Wright took part in qualifying runs and, despite crashing in practice, managed to make the cut for the big race, earning 36th place in the preliminaries.

Of course, a closer examination might have prompted more questions. Wright clocked a fairly lackluster speed during qualifying, around 187 mph. Ironically, that was the year at Talladega that Benny Parsons became the first driver to ever hit 200 MPH in qualifying.

His lack of speed became his ultimate undoing. NASCAR officials black-flagged him after 13 laps for driving below the minimal speed of 180 mph, ending his bizarre participation in the race.

“He went to the garage area and left the track and left his car behind sort of like, ‘I’m gonna escape this place,’” Sterling Martin told ESPN.

In addition to the car, Wright was also alleged to have left behind a string of unpaid bills and bounced checks related to his racing shenanigans. Years later, NASCAR reportedly hired a private detective to track down the apparent fraudster, but the sleuth was unable to track Wright down, and eventually, NASCAR gave up the search. The case took an unexpected turn last year when racing journalist Larry Woody, who actually met Wright at Talladega that year, was contacted by someone claiming to be a relative of Wright, providing just enough details to substantiate that Wright, now in his 70s, was still alive and living under another name.

Wright Reemerges

Then, like the Phoenix rising from its ashes, Wright climbed out of the shadows to speak with NASCAR journalist Rick Houston on The Scene Vault Podcast. In addition to confirming his identity as "Larry Wright," he offered his racing suit from Talladega as proof, matching similar suits that others had found in photos from the 1982.

The now 73-year-old Wright corroborated he purchased the car from Marlin, but added he did so under the condition that Coo Coo Marlin’s crew pitted the car at its debut race and painted it black. Wright said he wanted the No. 34 painted on the side to honor bootlegger-turned-racer Wendell Scott, who went to become the first African-American to win a race in the Grand National Series, NASCAR’s most elite level.

"I remember pulling into the infield that day and standing at the end of the track and looking down it,” said Wright in the podcast interview. “And I looked over at my brother, and I said 'Lord, have mercy, there ain't no way! ... You think about holding that car, the pedal flat on the floor all the way around this track, that straightaway's almost a mile long. How much can that car gain before you go into that turn?' And that was my first thought.”

"I got off by myself that day, and I said 'Lord, I'm down here, but I'm gonna need some help.' And I didn't tell nobody else that," he added.

Wright disputed claims that he'd run out on his debts, characterizing any financial missteps as unpaid bills that stemmed from sponsors, not him, backing out of planned deals.

"The people that was puttin' money in the car to catch up, these promised notes or bills, didn't,” Wright said. “When we didn't get to run the race, they just quit. So, it was left on me by myself.”

“If you could find somebody that said that I owed them $30,000, you tell them, and I'll face 'em. I want to see who they are, and I want to know how it come about. If that makes them stutter, you know what I'm talkin' about, okay?"

Whatever the real story may be, the mystery surrounding the bizarrely epic con still stands the test of time, igniting the curiosity in all of us.

“I just can’t believe the guy did what he did and scammed a bunch of people and got onto the racetrack and run the race,” Dale Earnhardt Jr. said in an interview on NBC before Wright's re-emergence. “How do you do that?”

“It’s kind of this fun mystery. Maybe we don’t ever want it to be solved.”